- Gems

- Lock of Audubon hair framed

Lock of Audubon hair framed

$3,500.00

A keepsake from John James Audubon to Henry Ward, 1832

Lock of Audubon hair framed and collected by Audubon’s taxidermist Henry Ward (provenance based on included documents).

Never examined out of frame.

Description

Audubon was known to be very proud of his long hair, and it played an important role in establishing the persona he adopted of “The American Woodman” when he arrived in Europe in 1826, seeking a publisher for The Birds of America. Audubon gave his wife keepsakes he made from his own hair, so it was not surprising to see the following listing in an auction catalog in the Spring of 2011.

[AUDUBON, John James (1785-1851)]. A lock of hair identified as Audubon’s (manuscript label), mounted with an envelope annotated ‘Given to me by J. James Audubon Esqr at the Revd John Bachman[‘s] June 5 1832 Charleston’ and another related note, framed and glazed.The mention of Bachman and the date gave the item greater credibility, and I thought there might be an interesting story associated with it. In early June of 1832, Audubon was in fact in Charleston and staying with John Bachman. He had just returned from a 6-week cruise on the Marion to Florida where he had drawn and collected birds for The Birds of America. Accompanying him on this trip were George Lehman, his artistic assistant, and Henry Ward, a taxidermist whom Audubon had brought with him when he came from England the previous year. Both men were discharged at the end of this trip. Lehman returned to Pennsylvania, where Audubon soon followed, but Ward stayed on in Charleston, Bachman having facilitated his employment with the Museum of Natural History there. $3800.

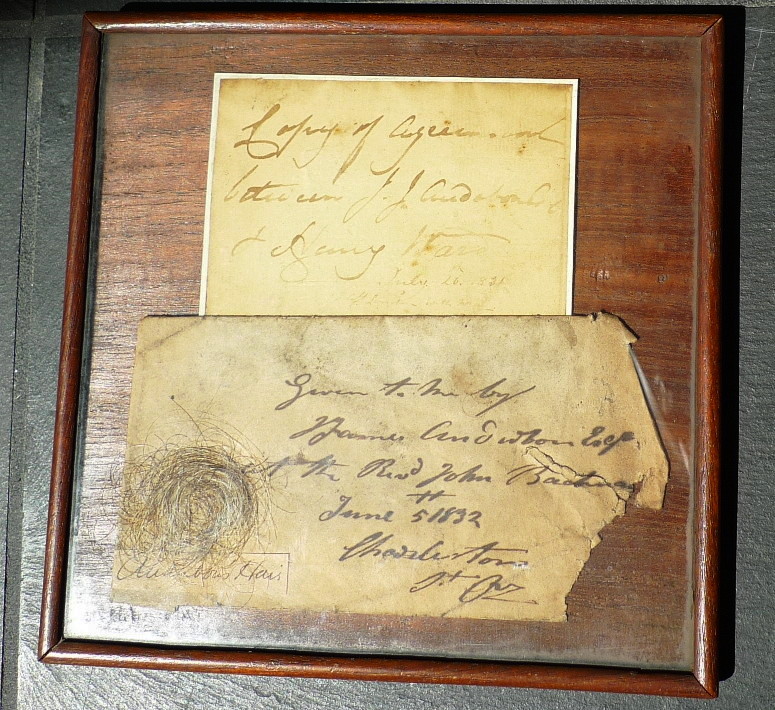

Below is a photo of the framed lock of hair and accompanying documents with a description and discussion of the piece, plus some information on Henry Ward.

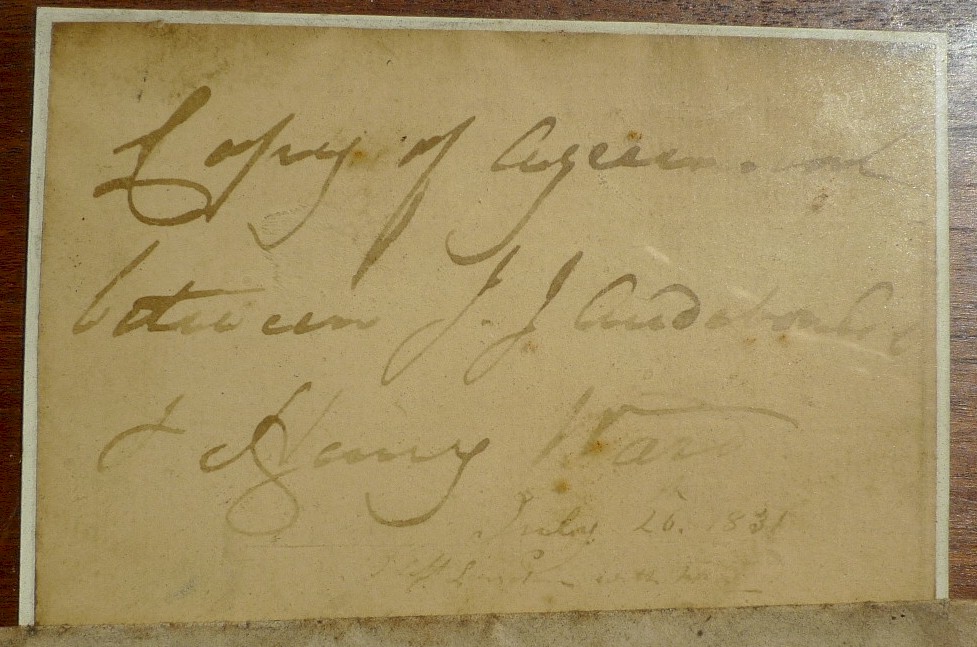

Item #1. The top item is a piece of laid paper mounted on cardstock. In one hand it reads

Copy of Agreement [?]

between J. J. Audubon [Esq?]

& Henry Ward

In smaller writing and in faded ink

July 26th. 1831 /

I left London with Mr. [A?]

The inclusion of this piece of mounted paper in the frame strongly suggests that the owner of the hair was Henry Ward. The “I” who left London is presumably Henry. The Audubons had booked passage on the Columbia, scheduled to sail July 31, 1831 from Portsmouth to New York (Streshinsky, p.407), so the timing would be consistent with Audubon’s travel plans.

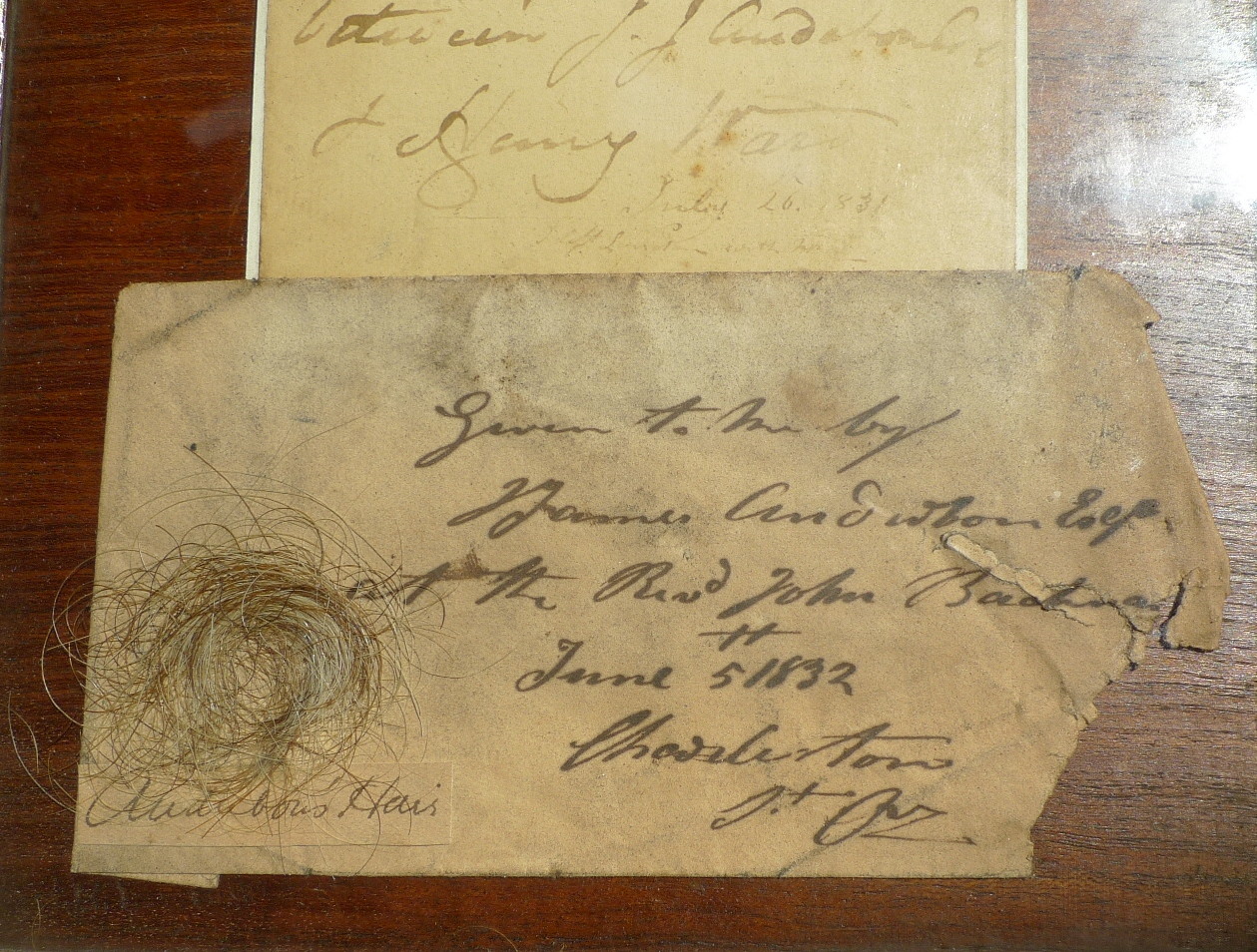

Item #2. Envelope (or other paper) against which the hair is placed and in which it was apparently stored. It seems reasonable to hypothesize that the envelope is in the hand of Henry Ward.

Given to Me by

JJames Audubon Esqr

at the Revd John Bachma[n]

June 5 1832

Charleston

St[?] [Indecipherable]

The last line may conceivably be some sort of abbreviation for South Carolina.

Item #3. Hair with Label reading Audubon’s Hair

There are two groups of writing in Item #1 that seem to date to different times. I do not believe they are in the same hand, but others may disagree. The name “J. J. Audubon” reminds me of Audubon’s handwriting, although the “A” and small “d” in Audubon are not characteristic of Audubon’s formal signature at the time. The Js, however, are very typical of Audubon’s hand. Audubon wrote his name using many different styles of writing over the years, and it is possible to locate examples of his signature where the A and d are similar to what is shown here. Whether or not this is Audubon’s handwriting, it appears to be something related to the agreement that sent Ward on his way with Audubon. If this is supposed to be a memento or keepsake of Ward’s time with Audubon, the inclusion of this piece of writing makes sense.

The handwriting at the note on the bottom seems similar to the handwriting on the envelope, particularly the upper case J’s and the upper case M’s. If the writing on the envelope is Henry Ward’s, then it is likely that this notation would have also been Ward’s, but there is no way to know when it was written (July 26, 1831 or some time later).

The label looks as if it may be in a different hand than the other writing. If this is Henry’s keepsake, it is possible that someone else made the frame and/or the label for him. And finally the hair itself — note the mixture of colors. Audubon was 47 at the time. In the future, Bachman would tease Audubon about his appearance upon his return from Florida: “As I saw you…as you came from Florida…your beard, two month’s old, was as grey as a Badger’s. I think a grizzly-bear, forty-seven years old, would have claimed you as par nobile fratum.” (Letter of Bachman to Audubon, quoted in Arthur, p. 415.)

ABOUT HENRY WARD

Henry Ward was the youngest son of taxidermist J. H. Ward who had been employed as “bird-stuffer to the King.” (Shuler, p.3.) In fact, both of Ward’s parents were involved in the work, and trained all three of their children, two sons and a daughter, to the profession. Audubon would have his ups and downs with Ward, but apparently Bachman liked Henry well enough to assist him in obtaining the Museum job after he left Audubon’s employment. Ward was a drinker, a spendthrift, and apparently a rogue. He kept the proceeds from items he sold that rightfully belonged to Audubon, and he stole both from the Museum and from Bachman. He was fired from his job in Charleston in late 1833. In 1834 Ward married, and Audubon passed on by letter to Bachman news of his latest tricks, including the stripping of plumes from heron skins for the fashion trade and the sale of the mutilated skins to collectors. Shuler writes, “Knowledge of this unscrupulous behavior should have ended Audubon’s patronage, but it did not. Presently Audubon began to correspond with Henry Ward, and by 1835 found it in his heart to warmly recommend that John Children, director of the British Museum, hire the scamp, a generous favor by comparison to the treatment of Lehman, whom Audubon brusquely fired at the conclusion of the Florida voyage and shunned long after. Perhaps Ward’s connection with the Crown and English ornithologists made it seem worthwhile for Audubon to overlook Ward’s faults.” (Shuler, p.109.)

After working several years for another London firm, Henry began his own taxidermy business in 1857. When they had reached the appropriate age, he brought his sons, Edwin and Rowland, into the business. Eventually both young men would strike out on their own. Edwin would be employed by royalty, while Rowland would go on to have extraordinary success and influence as a specialist in big game trophies. Henry died in 1878. In 1880, Rowland published what would be the first of several books. Titled The Sportsman’s Handbook, he dedicated the book to his father with a moving tribute to his father’s skill:

This book is dedicated to the revered memory of the late Henry Ward of London, (my father), whose eminence as a practical taxidermist, and as traveller, sportsman, and naturalist, I prize like an inheritance, and affectionately emulate.

In his preface, Rowland wrote of his family’s involvement with taxidermy:

My grandfather was a practical naturalist; my father, the late Henry Ward, became eminent in the same way, but with some remarkable advantages, having travelled much in pursuit of his profession in both hemispheres, and notably as the companion of Audubon, when that distinguished man was so greatly enriching and extending the field of natural history.

In researching Henry Ward, I found frequent mention of his connection to Audubon. The connection was important to him, possibly because it enhanced his professional credentials, or because he sincerely valued what he learned in his work with Audubon. Although Ward’s behavior as a younger man (both before, during, and after his travels with Audubon) was irresponsible and worse, in the long run Audubon maintained a friendly relationship with him. That Henry placed a high value on his experience with Audubon (whether out of sincere sentiment or because of Audubon’s fame) is clear from the careful construction of this keepsake. The relationship with Audubon was obviously prized by his family as well, and it is not surprising that this interesting piece has survived to the present day.

REFERENCES

Arthur, Stanley Clisby; Audubon: An Intimate Life of the American Woodsman, Gretna LA: Pelican Publishing Company, Inc, 1999. (First edition published 1937.)

Shuler, Jay; Had I the Wings: The Friendship of Bachman & Audubon, Athens GA: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Streshinsky, Shirley; Audubon: Life and Art in the American Wilderness, New York: Villard Books, 1993

Ward, Rowland; The Sportsman’s Handbook to Practical Collecting, Preserving, and Artistic Setting-Up of Trophies and Specimens, London: Rowland Ward and Simpkin, Marshall, & Co., 1880.

________

Additional information on the Wards came from the following websites. (Unfortunately, several of these pages are not available anymore.) The first website below includes photos showing surviving examples of Ward family taxidermy, most of the specimens by Rowland, but also some by Henry and Edwin. The Wards seem to have had a family habit of using their middle rather than first names; as is often the case, the same small set of names reappear generation after generation. For example, Henry’s first name was actually Edwin (but he was known as Henry); his eldest son’s full name was also Edwin Henry Ward. Rowland Ward was actually named James Rowland Ward, and used the James for a short period in his professional life. This has led to some confusion about the identity of individual family members; my practice has been to use the names most commonly encountered in print and on the Internet. Of course the name HENRY WARD is of the greatest relevance in any discussion relating to Audubon.

http://www.taxidermy4cash.com/Rowlandward.html

http://www.southpacifictaxidermy.com/Wards_of_London

https://rowlandward.com/about/

Related products

-

Proof print of Florida Rat

$5,800.00 -

Three uncolored Havell prints — SOLD

INQUIRE FOR PRICE -

Uncolored Havell PL 6 Wild Turkey — SOLD

INQUIRE FOR PRICE

All items subject to prior sale.

Sometimes a listed item will no longer be available but I can often locate another copy.

minniesland.com, LLC is located in the Washington DC metro area. Visitors by appointment.

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy

All content copyright © minniesland.com, LLC | Moonlit Media